This post is something of a sequel to this one.

I'm halfway through season two of The Wire (just finished "All Prologue") and I've got some more thoughts on it and David Simon's other HBO production, Generation Kill (thoughts which of course apply to television and to some extent narratives in general as well).

What strikes me now, especially after getting into Generation Kill, is that the problem I attempted to describe previously already has a perfect title, albeit one not widely used: the "tragedy of verisimilitude". Coined, as far as I know, by Battlestar Galactica's James Callis in a "roundtable" podcast of several of the show's actors and crew (a fascinating, albeit very long, discussion, you can get download it from SciFi's Battlestar site, which unfortunately prevents more direct linking), he lamented that Battlestar's oft-praised dedication to realism (or more accurately verisimilitude) was occasionally a burden, when the principles of physical reality (or the expectations of the audience) made simple stories needlessly complex (or worse, made them impossible to convey believably).

While the problem occasionally rises on Battlestar, it's much more prevalent on the much more grounded Wire and, in a twisted, more acceptable fashion due to its semi-nonfictional nature, Generation Kill. The second season of The Wire begins with the main characters of the first season, who were pulled from various disparate police units to serve on a special detail, scattered into the wind. McNulty is working the boat; Freamon is in Homicide; Kima has a desk job; Daniels is in the basement; etc. The first episode juggles the ongoing fates of these characters while continuing the story of Avon Barksdale's similarly scattered drug crew and introducing an entirely new set of characters at the Baltimore docks (not to mention beginning a plot, although that's clearly, as always on The Wire, a secondary priority). It's a clusterfuck of too many characters, too much to carry, and yet it works in a twisted way, because this is what happens. People move on, with their jobs and with their lives, and the attempt to follow that, rather than unrealistically but more simply keep them together, or bring them back together on another detail for a new case.

The new detail in season two: actually the same as the old one. (The Wire, 2003)

The new detail in season two: actually the same as the old one. (The Wire, 2003)Which is exactly what happens, painfully slowly, over the course of the next five episodes. And this is where the tragedy of verisimilitude nearly broke me with The Wire. It's okay to want to bring all your main characters back; after all, that's what the audience (most likely) wants, and we'll forgive you for bending reality a bit in order to do it. It's also okay to play it realistically and have people actually move on; the audience will hopefully appreciate that that kind of realism is seldom seen on television and decide it's interesting enough to keep watching. It's not okay to try to mix the two, however; all that ends up happening is a mush of boring scenes, drawn out far too long. Once the audience knows what's going to happen, almost always the best thing to do is to cut right to it.

(Actually, one of my favorite narrative techniques is to make sure the audience knows what's coming and delay it as long as possible, making the tension arise from knowledge rather than mystery, but that's hard to pull off without it being boring. One of the best, relatively straight-forward examples of this that I know is the Battlestar episode "Pegasus". From the moment Cain says, "Welcome back to the Colonial Fleet," the audience knows how the episode is going to end; the episode is brilliant because it gets the audience screaming for Adama to stand up to Cain the whole episode as he keeps lying down, increasingly desperately trying to avoid a confrontation.)

Ironically, of course, the problem with The Wire in this instance isn't its commitment to realism, but rather its attempt to hide an obvious puppeteering of the story by drawing it out with the bureaucratic stupidity that's such a hallmark of the series. And it doesn't work. Luckily, the rest of season two--the dockworkers and the continuing story of Barksdale and co.--is for the most part strong enough to carry this bullshit (although if asked to recount the actual plots of the episodes, all I could probably tell you was "things happen", because there's even less regard for episodic structure here than there was in the first season.) Ah, well. This is the show David Simon wanted to make.

Generation Kill presents a rather different and more intriguing variation of the tragedy of verisimilitude. Based on a nonfiction book that as I understand is largely just a diary-esque narrative of the events witnessed by embedded journalist Evan Wright, basically every plot element and even much of the dialogue is apparently taken directly from the book (and, therefore, directly from real life). This worked amazingly well for the first episode. (As an aside, I'd also like to comment that while the first episode of Generation Kill is as devoid of plot as the worst of The Wire, I found it much more captivating. I think this is because Generation Kill is actually presenting something that's more unknown, although I admit that it could well be just because, despite my pacifism, I still harbor a boyish fascination of the military.) As the miniseries has gone on, however, it's become more and more of a problem.

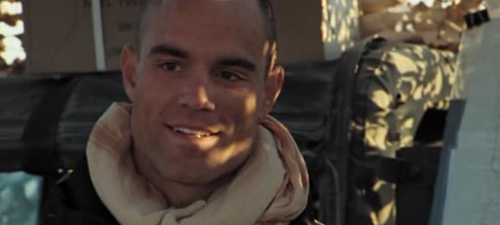

"Encino Man" (Brian Wade) in Generation Kill (2008)

"Encino Man" (Brian Wade) in Generation Kill (2008)This is because, despite all the warnings against them in every guide to writing fiction ever, in real life there are people who are, from most perspectives, one-dimensionally fucked-up. Generation Kill's "Encino Man" (for a while I thought they were deliberately avoiding his name, but it finally got used in the last episode) is one such person. He's a moron. He's incompetent. He tries to call in artillery fire on his own troops but fails because he doesn't know how to properly call in the coordinates. He is praised for this action by his superiors because it is blatantly wrong. Someone could write this in fiction as perhaps a bitter satire of bureaucracy and stupidity, but not as a straight-faced drama expecting to be taken seriously. It's ridiculous. (And I won't even try to describe "Captain America" . . .) Yet Generation Kill plays this absurdity straight, because it has to, because it actually happened.

And because it actually happened, it works, in a twisted sort of way. While watching the past two episodes I constantly found myself in a state of disbelief and constantly correcting it by reminding myself that all of this was real. It's a strange feeling (although one I'm not unfamiliar with--sometimes I look up at the sky and think it looks fake because it seems too flat. "It's just a bad skybox texture," I tell myself before realizing how fucked up I am.) Many people are now familiar with the absurdities within the government that led to the Iraq War and continue to this day, absurdities that would break the suspension of disbelief in any work of fiction, but it's surreal to realize that the same absurdities applied all the way down the line (and all around us, everywhere).

Perhaps that's the real tragedy of verisimilitude, though. Not when fiction fails because it's trying to hard to be real, but when fiction has so grounded us and so reinforced our expectations of reality that reality itself starts to seem unreal. I'm reminded of another situation on Battlestar, a sequence involving two people ejected into space without spacesuits. Scientifically, a person can survive in a vacuum without containment for up to two minutes without severe injuries; but fiction has so grounded in people the idea that exposure to the vacuum of space means instant death (via explosive decompression) that the people behind the show struggled to make the audience accept it. In that instance, of course, it wasn't that big of a deal--just a minor scientific discrepancy that's unlikely to actually impact anyone's life--but in these greater, everyday situations, when we look at the people we elected to serve us and find their actions unfathomable . . . what hope have we of doing something to change what we cannot understand?

Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld: too insane to be taken seriously? (source)

Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld: too insane to be taken seriously? (source)I mean, perhaps the success of the Bush administration has simply been that's it is, like a mad scientist's plot in a bad sci-fi movie, so insane it actually works. They were so far off the edge of reality that no one could do anything but watch, mouth agape, in horror and disbelief. Hyperbole, of course, but I do seriously wonder if some of the lack of opposition to the monstrosities that have been perpetrated in the name of the United States arose simply from an inability to process what was actually happening. (And then of course, I wonder, could the same be said of other monstrosities? How many German officials helped perpetuate the Holocaust simply because, safely distant from the death camps, their minds just shut down and didn't conceive of what was actually happening?)

That's not an excuse, of course. Basically, all I'm saying, with different words, is that the people involved in heinous crimes refuse to face the reality of what they are doing, which is nothing new. I recall a comment by Adam Hochschild in King Leopold's Ghost comparing similar testimony of those involved in the Congo genocide and those involved in the Holocaust, both claiming that because they never actually pulled the trigger, or pushed the button, or whatever, they felt they couldn't actually be held responsible for the deaths. The distance allowed them to separate themselves from the crime. The distance they meant what more-or-less physical; what I'm describing here is just a psychological distance, which is just as, if not, more effective. And we're all perpetrators of it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment