This is a strange post.

First, a disclaimer: I don't like grand statements about "our times", how they're different or more important than what came before. I think history mostly repeats itself, with minor variations, because despite all our percieved advances humanity hasn't actually changed much since history first became history. Please keep this in mind, for while I try to avoid hyperbole, I'll doubtless engage in some of it anyway.

The current state of the United States is--and here's probably a moment of hyperbole--precarious. I won't be so presumptious as to argue this is a recent change; the United States has never been a great country (except in the sense of important), and that recognition, too, is nothing new. In fact, that's what concerns me the most about recent years. During the Bush administration the executive branch has become a bloated, corrupt arm that has seized as much power as it can, the legislature, even with a supposedly majority opposition, has laid over and played dead, and the judicial branch has publicly become a joke. The Constitution has been shredded, torture has become common-place, and prejudice, manipulation, smearing, and outright lying have become the order of the day.

Having finished the first season of The Wire (and the first episode of season two), I think I've figured out what my problem with it is: I'm not engaged by the characters. I don't mean to say that I don't like The Wire; I think it is brilliant, and great, and powerful, but so far it isn't the best show on television to me, because I don't love it. That sounds cheesy and it's about to get worse. There's no beauty in The Wire (for me). I am cognizant of the quality of what I'm watching, but I don't care.

As a writer I'm a character guy. My first priority in a story is always making the characters true and real; while of course I think about themes and motifs and structure and mechanics and what have you, if it undercuts the characters, it goes. On The Wire, I can't help but feel that the characters are working for the story and not the other way around. A part of it is likely simply that the characters are for the most part quite pedestrian--McNulty, setting aside the quality of the series and simply looking at the substance of his character, is a character I've seen a thousand times before in nearly every cop show ever: self-righteous, arrogant, intelligent, divorced, battling with his wife for custody, fucking another woman. This is more-or-less the sum total of his character at the end of season one. There's nothing interesting here. And the same goes for almost all of the characters. (I find Stringer Bell fascinating, but that may just be me.)

If you somehow weren't aware, season two of Mad Men premiered last night. The episode was everything I expected and hoped for and more, with a couple of surprises along with the general thoughtful evolution of characters that have aged more than a year since we last saw them. (Season two begins in February 1962; I believe season one ended Thanksgiving 1960, although I'm not as sure as I'd like to be.) What struck me--what has always struck me about Mad Men, since I watched the first episode, even as I have grown accustomed to it--was the pacing. Mad Men is a brilliant show, and while these are of necessity rare, it is by no means alone. I do believe, however, that Mad Men is unique, or nearly so, among television shows in its pacing. At the very least, I have never seen another show like it in this regard.

When searching for a way to describe Mad Men to friends who have never seen it, the word that almost always comes to mind is "pensive". So much of the show it seems is not in the dialogue or the actions but in the inaction, the moments of quite solitude when characters simply stare off in the distance, lost in thought. Of course, describing the show like this usually makes it seem boring and dull, but because of the acting and the writing it's not. Because Mad Men is a show about characters, more, a show about characters who are trapped in lives they do not want, in a structure and society they do not like but nonetheless uphold like some kind of nation-spanning Abilene paradox, we understand why they must take a moment, or many moments, to contemplate how fucked up their existences really are (and drink a hell of a lot of alcohol).

John Slattery as Roger Sterling in Mad Men (2007).

John Slattery as Roger Sterling in Mad Men (2007).And it couldn't be done any other way. If Mad Men were a fast-paced show about action and snappy banter, full of people walking down hallways, issuing quick orders, and exchanging rapid barbs, the characters would never get anywhere, because without those moments of reflection they would never come to the piercing self-awareness whose tragic juxtaposition with the flashy, glamorous action of the ad agency is the heart of the show.

I don't mean to say that such a fast-paced show can't have strong characters--Battlestar Galactica has proven that many times over. Although now I can't help but wonder, considering other things as well, if Battlestar's characters really came across as well as Mad Men's do in its first season. I suspect the answer is no, but I think that's more because Battlestar, as much as I like to think of it as a character drama (and the people behind it, according to press, do, too), in many ways it's not, or at least it's trying to do a lot more than just character drama, and it loses some of the character development in order to further those other goals in the limited time that it has. However, I think this, too, ties into pacing, because could a show really focus on its characters without a slower pace that allows them moments of reflection? A character study or portrait, perhaps, but not any show in which the characters were expected to change and grow, I think.

Pacing doesn't just apply to the style and structure of individual episodes, of course. The pacing of seasons--or even an entire series (here's looking at you, Babylon 5)--also deserve consideration. Episodic series, obviously, don't have any real seasonal or serial pacing, but shows with long-term arcs (sometimes referred to as "novelistic" series) do. Several years ago, following the unlikely runaway success of Lost, "arc-based" shows briefly became a fad on the major networks, with shows like Threshold and Invasion trying to repeat Lost's success by replicating its long-term story (with almost no success). On cable and premium television, of course, there was nothing new about arc-based shows, and arcs have been a fixture even of network television for decades. And the existence of arcs themselves doesn't necessarily constitute a sense of pacing, although it does force those behind a show to at least consider it (I hope).

One of the best examples, or at least one of the most extreme, of such seasonal pacing is The Wire. In the past couple of days I've watched the first ten episodes of season one. The Wire's creator and show-runner, David Simon, has famously compared each season of The Wire to a novel, with each season telling a single long, over-arcing plot and (somewhat infamously) early episodes being devoted (as in the early chapters of a novel, the analogy goes) to character development and exposition rather than direct plot development. I'm not entirely sure I agree with the "novelistic" moniker: yes, it's closer to a novel than anything else I've seen on television, but nonetheless it's not a novel, and the comparison tends to be used more to implicitly reference the supposed superiority of literature to television rather than any real commentary for the structure of the show.

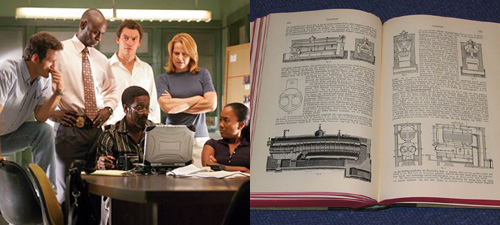

At left: The Wire (2008). At right: a book (photo by Lars Aronsson).

At left: The Wire (2008). At right: a book (photo by Lars Aronsson).Setting that aside, however, The Wire does demonstrate a very deliberate and slow seasonal pacing that marks it from other shows. After watching as much as I have, I'm honestly quite glad that I never tried to watch this show as it premiered, because the individual episodes are so obviously simply a part of a larger whole that I'm not sure how satisfying it would have been to watch only one a week. It's not uncommon in The Wire for details mentioned in one scene of one episode to come to bear relevance on the plot three, four, or much more episodes later. Several times, such details are startling "cliffhanger" revelations in the final scene of an episode, which are then never mentioned and have no obvious impact on the next episode. Watching it as I am, in close procession, this isn't particularly bothersome, but it does at times feel like sloppy television. The Wire is supposed to be the best show on television, and I'm not denying its brilliance, but even the best have flaws, and to me this seems one of them.

I don't mean to degrade arc-based plotting in general; in fact, quite the opposite: I love arc-based shows and strongly prefer them over episodic series, which tend towards popcorn entertainment. (This is intrinsic to the nature of episodic television, I think: in order for a show to be episodic, to begin with the same premise every episode, it must end with the same premise every episode. Nothing can change, leading usually to the frequent usage of a "reset button" that fixes whatever changes might have occurred as a result of the episode's events and prevents any real development of the plot or characters.) But the episodic nature of television cannot be ignored or denied.

A television season is not a thirteen-hour movie (and even a thirteen-hour movie would have its own special pacing requirements rather than simply being a feature length film extended so many hours); it is a progression of thirteen, or twenty, or however many episodes, each of which are a contained unit. While nowadays sales of television DVDs are strong and growing, and many people are encountering critically acclaimed but popularly ignored series for the first time in this format that obviates some of these pacing concerns, this is still true. (Watching a season on DVD could be directly compared to watching a thirteen-hour movie--but again, that's not the same as a regular movie.)

Mad Men knows this, as does Battlestar. I honestly think the best example of such episodic yet arc-based television may be the first season of Veronica Mars, a critical darling that skirted cancellation for three years before finally (and tragically) losing the battle. While the following seasons were questionable as to their greatness, the first season is to me among the best ever on television, and it perfectly balances a season-long mystery plot, with a slow progression of clues, red herrings, and true revelations, with cleverly done individual mysteries in each episode, along with seasonal character development and well-developed guest characters in individual episodes. While I watched the first (and second) seasons on DVD, I never felt that the series would have been difficult to watch weekly (and I did watch the third season weekly, which handled the structure about as well, if the actual plots and characters were not as well-done).

Kristen Bell in Veronica Mars (2007).

Kristen Bell in Veronica Mars (2007).Ironically, the first season of Veronica Mars was developed from an unpublished novel by creator Rob Thomas; supposedly most of the progression of the seasonal mystery was taken more-or-less directly from this novel. (This also to some degree explains the quality of the first season's big mystery in comparison to the next two, which were developed on the time of the series.) But Veronica Mars is not a novel, and doesn't try to be, and that is its strength. I have never seen anything pointing one way or the other, but I assume that the vast majority of the individual episodic mysteries were written specifically for the series and the general pace of the novel greatly slowed in order to accommodate the new format of the story. It is because Veronica Mars recognized its format and didn't try to pretend to be something else--regardless of its origins--that it succeeds so well (in addition to brilliant writing and acting, of course).

Recently I saw Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull in theaters for the second time. I'm a true Indiana Jones fanatic--hung above my desk, right next to my computer, are all four movie posters, framed--so when I saw the film for the first time, most of my response to it was as from the view of a fan who had read over ten years' worth of rumors and reports (basically, from when I first got internet access) about a fourth Indiana Jones movie. Even so, my analytical brain went into action when I saw it the first time, and there were a number of things that intrigued me about the film. I don't consider it a particularly good movie: I think it's certainly the weakest of the four, and what I have to say here is not meant to elevate the quality of the movie in any way. But there were things that seemed to deserve further thought than usual with the simple popcorn entertainment that I consider Indiana Jones, and so on my second viewing I went in with an eye for something more. Spoilers from here on, for all four Indiana Jones films.

What I realized, or decided, or constructed, was that The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is not just a new movie about Indiana Jones; it is a movie about the death of Indiana Jones--the idea of Indiana Jones, the persona separate from the person of Henry Jones, Jr. Upon thinking about it, this is really strikingly obvious. After all, the film ends with Indiana Jones getting married, something that could not even be contemplated with regards to the Indy of the original trilogy, and an almost literal passing-of-the-hat to Indy's son (although "Mutt Jones and the whatever" doesn't seem to me as something that would play well on a movie poster). But it's not simply the death of one man's adventuring career, it's the death of the entire idea of adventuring for "fortune and glory" (as Indy famously quips in The Temple of Doom), of death-defying stunts against insidious villains, of mysterious artifacts of ancient and unknown power. More than that, it's the death of the unrepentant American optimism of the thirties and forties, when Americans believed in an American dream despite the Great Depression and later believed in their absolute righteousness in the fight against the Nazis, so gloriously demonstrated in the adventure serials that the original Indiana Jones trilogy were inspired by. The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is about the end of an era.

For years there have been (at least to my perhaps biased perceptions) two shows that have dominated television critics' articles as the "best shows on TV": Battlestar Galactica and The Wire. I've watched Battlestar since the beginning (and fallen completely in love with it, and become known as something of an evangelist for it), but I was never able to watch The Wire because it's an HBO show. Recently I've finally been able to start watching it--so far, only the first episode--and I've been trying to put my reaction into words. It's a very weird thing, to read about the greatness of something for five-odd years before finally getting to experience it; it's a recipe for overhyped expectations, disillusionment, disappointment. I'm not disappointed, so far; but disillusionment would be a fair assessment. I don't mean that in a bad way--the first episode was great--and to be honest it doesn't so much have to do with the critical praise as it does with the show it's paired with.

Battlestar is a show about the nuclear annihilation of humanity by killer robots and the human survivors' attempts to find a new life and a new way to live. It's a character drama of the highest caliber, yes, but it's also a show with space battles and nuclear showdowns and sex (surprising amounts of sex, really) and all a manner of infantile geek fun. Watching Battlestar, I get to indulge both the intellectual, artistic, philosophical brain and the instinctual, visceral, kiddie brain. And that's not just a great package, it also allows the show to occasionally transform visceral fantasies into their horrifying realities in a moment, twisting the infantile pleasure of watching spaceships blow up into a shocking moment of self-awareness. Which is great and lovely and awesome.

That's not what The Wire is. This should be obvious, of course. The Wire is, after all, a cop show. It's not about nuclear showdowns and killer robots. But somehow, in the years I spent hearing about the other best show on television, I connected the two in my brain, or at least got used to the idea of great television being both entertaining and intelligent. I don't mean to say that The Wire isn't entertaining (even though that's what I just said), but that--well, it's not visceral. There's nothing "awesome" (in the popular sense of explosions and sex) about The Wire, or at least not the first episode. It's very well-written and touches on a lot of important themes and says a lot of important things, but I didn't get a spectacularly wide grin on my face when I watched it like I do with Battlestar or even (to reference a previous post) The Dark Knight.

At left: "The Target", The Wire (2002). At right: "Exodus, Part II", Battlestar Galactica (2006).

That's not a bad thing, necessarily, of course. Or maybe it is. One of my other favorite shows is/was Firefly, the infamously short-changed sci-fi/western from Joss Whedon. Firefly and Battlestar have often been paired as the vanguards of a new type of science fiction. In the sense of "actually really good", that's true, but beyond that there's not a lot to compare them, I think. The striking thing about Firefly (although it's not really striking to anyone familiar with Whedon's work) is its method of combining moments of seriousness and comedy, transitioning between the two smoothly and elegantly, and using the combination of the two to elevate both of them to higher levels. (Whedon talks about this in the director's commentary to Serenity, the Firefly feature film.) Watching Firefly, the drama is more dramatic because of the comedy, and vice versa, much in the same way as the viscerality and intellectualism of Battlestar complement and elevate each other.

I used to just say Battlestar and Firefly were different shows and that's that. I still agree with the first part, but after watching a recent episode, "The Hub", penned by regular Whedon writer Jane Espenson I came to think there's more to say on the subject. (Espenson maintains a blog on writing that has discussed this subject in more detail and with her own expertise weighing in. I whole-heartedly recommend it for any aspiring writer.) While Espenson wrote several Battlestar episodes prior to "The Hub" (she's now a co-executive producer, I believe), this was the first in which a substantial amount of comedy is present. And it made the episode one of the most memorable of the series, as well as making some of the dramatic moments (particularly between the characters of Laura Roslin and Gaius Baltar, around whom most of the earlier comedy is based) strikingly poignant.

Battlestar attempted comedy once before, in a season one episode called "Tigh Me Up, Tigh Me Down". It's one of my favorites from the first season, and I think it's hilarious, but it's a very odd episode, very obviously different from the rest of the series, very obviously intended to be a comedy (albeit, in Battlestar fashion, a very, very dark one). "The Hub" is not like this: the humor doesn't stand out, and the episode contains some of the most serious and important scenes in the series.

At left: Edward James Olmos in "Pegasus", Battlestar Galactica (2005). At right: Adam Baldwin in "The Message", Firefly (2003).

I like Battlestar more than Firefly, but I'm the first to admit that a large part of that may be the fact that I have four seasons of Battlestar to love and not even one complete season of Firefly. I have often wondered if I would have liked Firefly more had it survived--a pointless question, taken superficially, but what I really want to know: is Firefly's style of blending comedy and drama (and not in the asinine "dramedy" that usually manages to accomplish neither, but in a more natural sense) better than the hardcore bleak blackness of Battlestar and (even moreso, it would seem) The Wire? Is the blending of the visceral and the intellectual on Battlestar better than the so-far almost purely intellectual of The Wire?

Since I'm posing the question, of course, I lean towards yes. I won't pretend that I'm sure of that. (And since I'm rather terrible at writing comedy, there's a part of me that would really prefer the answer be no.) But I think what the essence here is not so much comedy and drama, or the intellectual and visceral, but just the idea of combining, blending, mixing. I think that truth, what's right, is in general terms a matter of openness, acceptance, reconciliation. I won't explain fully here--because doing so would be an entirely other, very long essay--but I tend to see things in terms of apophasis (defining things through negatives, or just defining things, putting limits on them, categorizing, and so on) and entanglement (embracing differences, undefinability, the vagueness of existence, and so on). Society, structure, systems (not to mention "the plan") are apophatic, while life and reality is entangled.

Fiction, or art, or any construction (including what is generally termed "non-fiction") lies at an interesting point along this spectrum. As a construction there's an inherent amount of apophasis to a work--there is only what the creator created, right?--but in the end, like everything else, it always becomes entangled. Works come to mean much more than their creators ever intended. And to embrace that, to embrace the undefinability and not try to limit a work to one specific frame, is what's right.

That's a far cry from the difference between comedy and drama or between viscerality and intellectualism, of course. I don't mean to suggest that they're equivalent--or maybe I do. To be honest I'm not sure what I think about all of this. I'm basically just talking out of my ass and hoping to find a solution as I write. It hasn't worked--it rarely does--but I have, I think, managed to organize my thoughts on the subject better. And that will have to do for now.

This isn't a review; so if that's what you're looking for, go somewhere else. (Preferably to a theater, where you can buy a ticket to see The Dark Knight.) Nor is this a critical analysis, although that's closer. I think the best term for it would be a "response" to The Dark Knight--if only because that's a very general, almost meaningless term. This is my attempt to engage the film on level beyond "holy fuck, that was awesome" (although that is a perfectly legitimate response, and one I agree with completely). In case you haven't gotten the hint yet, there be spoilers ahead.

I'm going to delineate three phases I went through with The Dark Knight. I didn't actually go through three distinct phases--as with everything, these categories and definitions and limitations are mere approximations of the true, gradual, undefinable, limitless experience--but they're useful for what I want to do here, so bear with me.

The first phase, beginning shortly after the film started and continuing for several hours after walking out the theater, was the "holy fuck, that was awesome" phase. I sat in my car with a huge grin on my face, incapable of being distracted or annoyed by anything, completely overcome with joy at the experience of the film. I went straight from the movie to a party with many people who had seen just seen it that day or the night before (this was the Friday it was released) and spent a lot of time discussing the general awesomeness of the film as well as specific moments. (The scene where the Joker makes the pencil disappear seemed to be a favorite. I agree.)